Justice K.S. Hegde and Justice Honnaiah

Long before the Judgment of the Supreme Court in Maneka Gandhi vs Union of India, the then Mysore High Court had declared that right to go abroad is a fundamental right. It also gave third dimension to Article 14 of the Constitution of India. The entire judgment is reproduced here.

JUDGEMENT

Dr. S.S Sadashiva Rao and Others v. Union of India And others Karnataka High Court

Writ Petition 532, 534, 535 and 537 of 1965 decided on 30 September 1965

W.P Nos. 532, 534, 535 and 537 of 1965 under Article 226 of the Constitution of India to issue a writ of Mandamus directing the Respondents to issue passport to the petitioners to go abroad.

Advocates. Shri K. Jagannath Shetty for Petitioners in W.P 532, 535 and 537/65.

Shri G.R Ethirajulu Naidu and Sri V.N Satyanarayana, for Petitioner in W.P 534/65.

Shri B.S Keshava Iyengar, Central Government Pleader for Respondents.

JUDGES

Justice K S Hegde and Justice Honniah.

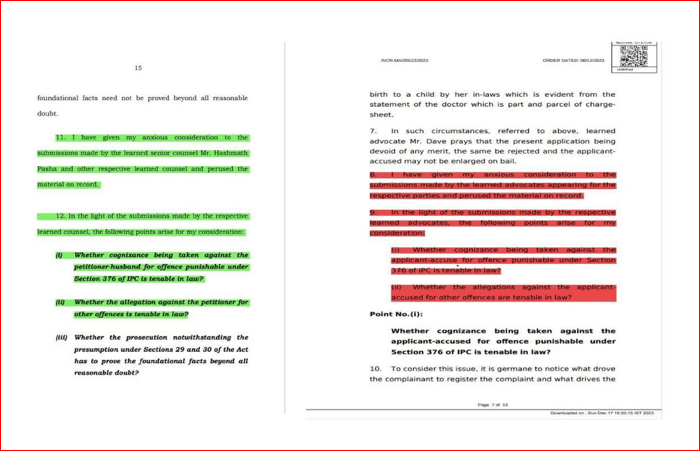

Order of the Court was made by Hegde, J.:—

The petitioners herein are Medical Graduates of the Mysore University. They are desirous of having higher studies, some in U.S.A, others in U.K For that purpose, each of them submitted an application to the third respondent (Regional Passport Officer, Madras) for a passport. But, their request has not yet been complied with in spite of repeated reminders. Hence, in these Writ Petitions, under Article 226 of the Constitution, each of them pray for a Writ of Mandamus or an Order or direction in the nature of Mandamus, to the respondents requiring them to issue him the passport asked for.

The petitioner in W.P No. 532/65 had submitted his passport application on 8th December 1964. He wants to proceed to U.S.A for higher studies in Surgery for a period of 5 years in Ellis Hospital, New York, U.S.A The petitioner in W.P No. 534/65 bad submitted his application for a passport, on 10th November 1964 to proceed to U.S.A for higher studies and training for about 5 years in Queens Hospital Centre at Jamaica, New York, U.S.A The petitioner in W.P No. 535/65 had submitted his application on 21st December 1964 for a passport to go to U.K for higher studies and training. He has been offered a post of Senior Home Officer in Lianfreehfa Grange Hospital, U.K The petitioner in W.P No. 537/65 had submitted his application for a passport to go to U.S.A with a view to have post-graduate training in Medicine for 8 years after one year’s Internship at St. Luke’s and Children’s Hospital, Philadelphia, U.S.A, under E.C TMG. of Chicago, Illinois, U.S.A

The petitioners had submitted their applications in the prescribed forms. Further, they had made available to the Passport Officer the information required. Till the filing of these petitions, they had not been told, why the passports asked for by them had not been given to them, nor were they informed that they will not be given the passports applied for. The petitioners complain that by refusing to grant the passports asked for, the respondents have contravened Articles 19(1)(d), 21 and 14 of the Constitution. They have given certain instances to establish their complaint of hostile discrimination against them.

In the counter-affidavit filed on behalf of the respondents by Mr. R.D Chakravarty, Under. Secretary to the Government of India in the Ministry of External Affairs, it is stated that the Government of India have laid down certain conditions regarding the issue of passports to Doctors desiring to go abroad. According to those conditions, Doctors who are in the employment of Governments or Semi-Government Institutions are granted passports for going abroad for higher studies, on their undertaking to return and serve their employers for a minimum period of three years. Other Doctors are granted passports for going for higher studies aborad only under the following conditions:

“(a) the doctor holds M.B.B.S Degree and has seven years’ experience.

(b) The Doctor holds M.B.B.S Degree with not less than 60% marks and has three years’ experience, and

(e) The doctor holds a post graduate degree like M.D or M.S of an Indian University.

It is not clear from the said counter-affidavit whether the afore-mentioned conditions have been prescribed under any Government Order. The counter-affidavit does not refer to any Government Order. The learned Counsel for the respondents was unable to tell us whether there is any Government Order, embodying these conditions. The document produced in proof of the conditions mentioned above, is the reply given by the Minister of Health in Parliament to Starred Question No. 145 put by Mr. Mulka Govinda Reddy, a Member of the Rajya Sabha (vide Annexure II). A reply of this character cannot be considered to have any legal force. It is in no sense an executive Order. Nor was it contended by the learned Central Government Pleader that the said reply can afford any legal basis if one is necessary, for refusing the passports asked for.

But, the main stand taken by the Central Government is that the petitioners have no fundamental right to go out of India either under Article 19(1)(d) or under Article 21 of the Constitution; those Articles merely guarantee a citizen freedom of movement within the country; our Constitution does not require the Government to facilitate any citizen of this Country to travel outside this country, no such right can be traced to any provision of a Statute or a statutory rule; while issuing a passport to any citizen, the Government is purely discharging a political function with a view to afford facilities to the citizen during his travel or stay abroad, a passport is nothing but a request made by the head of this state to all those whom it may concern to allow the bearer to pass freely without let or hindrance and to afford him or her every assistance and protection of which he or she may stand in need; it is purely within the discretion of the Central Government to issue such a letter of request or not; they cannot be compelled to issue such a letter; their discretion in that regard is neither controlled by the provisions of the Constitution nor by any other law; the petitioners have no legal right to ask the Government to give them passports nor has the Government a legal duty to issue a passport to any one. It was further contended that in view of the Proclamation of Emergency the petitioner cannot invoke the protection given by Article 19(1)(d). The complaint of inffringement of Article 14 was denied. Under, any circumstance it was said that there is no case for issuing a Writ of Mandamus.

Before cosidering the various contentions urged, it is necessary to ascertain the true character of a passport.

Under Entry 19 of List I in the Seventh Schedule Parliament is given power to legislate in respect of “passports and visas”. The only statute dealing with passports brought to our notice is the Indian Passport Act, 1920 (Act XXXIV of 1920). It was conceded before us that the issuance of passports for going out of India is not regulated by the provisions of that Act. That Act, as its title shows, is an Act, to take power to require passports of persons entering India. It has nothing to do with the issuance of passports to persons going out of India.

A passport issued is in the following form:

“These are to request and require in the name of the President of the Republic of India all those whom it may concern to allow the bearer to pass freely without let or hindrance and to afford him or her every assistance and protection of which he or she may stand in need.”

Dealing with “passports”, it is stated in Halsbury’s Laws of England, (Third Edition by Lord Simonds, 7th Volume, paragraph 568 at page 264) thus:

“Passports may be granted by the Crown at any time, to enable British subjects to travel with safety in foreign Countries, but such passports would clearly not be considerable so as to permit travel in an enemy’s country during war. Passports are issued by the Foreign Office or by diplomatic officers abroad.”

In Rockwell Kent and Walter Bribel v. John Foster Dulles . 2 L. Cd. 2d. 1204., Justice Douglas speaking for the majority of the Judges of the Supreme Court of America observed: “A passport not only is of great value – indeed necessary — abroad; it is also an aid in establishing citizenship for purposes of re-entry into the United States.”

There is no law in this country requiring a citizen of this Country to obtain a passport before going out of it. But then, Rule 3 of the Indian Passport Rules, 1950 framed in exercise of the powers conferred by section 3 of the Indian Passport Act, 1920, prescribes that save as provided in Rule 4, no person proceeding from any place outside India shall enter, or attempt to enter, India by water, land or air unless he is in possession of a valid passport conforming to the conditions prescribed in Rule 5. The cases before us do not fall within Rule 4.

In V.G Row v. The State of Madras the High Court of Madras took the view that the Rule in question did not apply to an Indian, citizen seeking to enter India. In view of the decision of the Supreme Court in Abdul Rahim Ismail C. Rahimtoola v. State Of Bombay . A.I.R 1959 S.C 1315. that view of the law must be held to be incorrect. The aforementioned Rule 3 applies both to Indian Citizens as well as to foreigners. Hence, whether the petitioners require passports to go out of this Country or not, without doubt, they do require validly issued passports to re-enter this Country. The case for the petitioners is that they are going abroad only for a temporary stay and they want to come back to this country after completing their studies. Therefore, as remarked by Justice Douglas in Rockwell Kent’s Case the possession of passports would be an aid to the petitioners in establishing their citizenship for purposes of re-entry into this Country. Rule 3 or any other Rule in the Indian Passport Rules, 1950, does not say that an application for a passport can only be made within certain time. The petitioners have a right to reside in this Country. That right of heirs is a fundamental right. In order to preserve and protect that right, they are entitled to take the required steps permitted by law.

It was conceded before us that either by law or by convention no citizen of one country is permitted to enter another country without a valid passport. Therefore, the contention of the Central Government that no passport is required to go out of this Country though technically correct, is opposed to the realities of the situation. If the petitioners have a fundamental right to travel abroad, which contention we shall presently examine, that right would altogether disappear if the Government is permitted to abrogate that right indirectly. It is well settled that no one can be permitted to do a thing indirectly what he cannot do directly.

The importance of travel abroad in the present age cannot be over-estimated. In a very illuminating Article in Columbia Law Review [Vol. LXI (1956) at page 47] under the Title “The Constitutional Right to Travel” Leonard S. Boudin, writes:

“Furthermore, it is the Government’s stated policy—the only one consistent with our democratic traditions—to encourage a welding together of nations and free intercourse of our citizens with those of other friendly countries. Upon its sucess depends that mutual understanding which is the only alternative to war. The vast amount of literature issued by the State Department, the International Exchange programme sponsored by it, and many other official acts of the United States attest to our recognition of this fact.

It is also significant that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations, includes among its provisions the right to travel. No country, however, has adopted the draft covenant on the subject, which alone might afford the legal basis for the enforcement of this right.

The final objection to limitations upon the right to travel is that they interfere with the individual’s freedom of expression. Travel itself is such a freedom in the view of the scholarly jurist. But we need not go that far; it is though that the freedom of speech includes the right of Americans to exercise it anywhere without the interference of their government. There are no geographical limitations to the Bill of Rights. A Government that sets citizens’ freedom of expression in any country in the world violates the Constitution as much as if it enjoined much expression in the United States.”

These observations apply in equal force to the conditions prevailing in this Country.

In Rockwell Kent’s Case, Justice Douglas dealing with the right to travel in foreign countries observed as follows:

“The right to travel is a part of the ‘liberty’ of which the citizen cannot be deprived without due process of law under the Fifth Amendment. So much is conceded by the Solicitor General. In Anglo-Saxon law that right was emerging at least as early as the Magna Carta Chafee. Three human Rights “in the Constitution of 1787 (1956). 171-181, 187 etc. Seq., shows how deeply engrained in our history this freedom of movement is. Freedom of movement across frontiers in either direction, and inside frontiers as well, was a part or our heritage. Travel abroad, like travel within the country, may be necessary for a livelihood. It may be as close to the heart of the individual as the choice of that he eats, or wears, or reads. Freedom of movement is basic in our scheme of values.”

Proceeding further, the learned Judge observed:

“Foreign correspondents and lecturers on public affairs need first hand information. Scientists and scholars gain greatly from consultations with colleagues in other countries. Students equip themselves for more fruitful care core in the United States by instruction in foreign Universities. Then there are reasons close to the core of personal life—marriage, re-uniting families, spending hours with old friends. Finally, travel abroad enables American citizens to understand that people like themselves live in Europe and helps them to be well-informed on public issues. An American who has crossed the occen is not obliged to from his opinions about our foreign policy merely from what he is told by officials of our government or by a few correspondents of American news papers. Moreover, his views on domestic questions are enriched by seeing how foreigners are trying to solve similar problems. In many different ways direct contact with other countries contributes to sounder decisions at home…Freedom to travel is, indeed, on important aspect of the citizan’s ‘liberty’. We need not decide the extent to which it can be curtailed”

In Rockwell Kent’s Case, passports asked for by Kent and another were refused by the Secretary of State for two reasons namely,

(1) that they were Communists; and

(2) that they had a consistent and prolonged adherence to the Communist Party line.

The Supreme Court ruled that the reasons given are not relevant under the provisions of the law regulating the issue of passports and consequently issued a mandate to the Secretary of State to issue them the passports asked for.

It was urged on behalf of the petitioners, and not denied by the learned Central Government Pleader, that the Government of India had issued instructions to the carriers and travel agents not to take on board passengers leaving India without valid passports and in obediance to those instructions transport facilities are not being afforded to any one who does not possess a valid passport to go abroad.

From the foregoing, it is seen that every one including a citizen of this Country requires a passport to enter this Country, by convention or law most if not all, Countries do not permit citizens of foreign Countries to enter their Country without valid passports; and in view of the instructions issued by the Central Government no transport facilities are being given to the citizen of this Country to go abroad if they do not possess valid passports.

In the Writ Petitions, in support of the reliefs prayed for, reliance was placed on Clause (d) of Article 19 as well as on Article 21 of the Constitution. But, at the time of the hearing, no reliance was placed on Article 19(1)(d) evidently because the proclamation of emergency is in force. Therefore, all that we have to see is whether Article 21 guarantees the petitioners’ right to go abroad. Article 21 says:

“No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.”

It was urged by Mr. K. Jaganatha Shetty on behalf of the petitioners that the expression “personal liberty” in Article 21 is an expression of wide import and that it includes all “liberties” other than those included in Article 19(1). It was said that right to travel abroad is one such right. The freedom of movement in whatever direction an individual may desire is his “personal liberty.” Article 19(1)(d) protects his freedom of movement within the Country. His right to go abroad is protected by Article 21. In this connection our attention was invited to several passages in the decision of the Supreme Court in A.K Gopalan v. State Of Madras.. Dealing with the scope of the expression “personal liberty” Kania, C.J observed (paragraph 12 at page 37):

“Deprivation (total loss) of personal liberty, which inter alia includes the right to eat or sleep when one likes or of work or not to work as and when one pleases and several such rights sought to be protected by the expression “personal liberty” in Article 21.”

Das, J. in the same case opined that “Personal liberty may be compendiously summed up as the right to do as one pleases within the law.”

Scope of Article 21 was considered by the Supreme Court in Kharak Singh v. State of U.P. In that case, there was different of opinion between the Judges so as to the respective scope of Article 19(1) and Article 21 and whether the “law” contemplated by Article 21 should satisfy the test of reasonableness prescribed in Article 19 or not. But all the Judges were agreed that the expression “personel liberty is an expression of wide import and it includes within itself all the varieties of rights which go to make up the personal liberties.” Speaking for the majority, Ayyangar, J. held that the words “personal liberty” in Article 21 are used as a compendious term to include within itself all the varieties” of man other than those dealt with in the several clauses of Article 19(1) in other words, while Article 19(1) deals with particular species or attributes of that freedom, personal liberty in Article 21 takes in and comprises the residue.

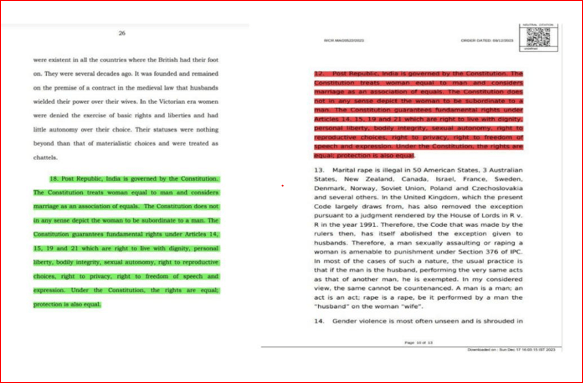

In England, as observed in Cooly’s Constitutional Limitations (8th Edition, Vol. 1, page 715), the right to personal liberty does not depend on any statute; but it is the birthright of every free man; as slavery ceased it become universal, and the Judges are bound to protect it by proper Writ when infringed. There is no gainsaying of the fact that the right to travel within the Country as well as outside it, is “personal liberty”. But, as mentioned earlier, so far as the right to travel within the country is concerned, it falls within Article 19(1)(d). Therefore, it is taken out of the scope of Article 21. But, the right to go abroad has not been included in Article 19(1)(d). Hence it must be held to fall within Article 21. Our view in this regard finds support from the decision of Tarkunde, J. in Chotthran Verhomal Jemuin v. A.G Kailsi.

We are unable to agree with Mr. B.S Keshava Iyengar, the learned Central Government Pleader that the “personal liberty” contemplated in Article 21 of the Constitution does not include within itself the right to go abroad. He contended that what is protected by Article 21 is the total deprivation of freedom of movement and not any restriction being placed on that freedom. In support of that contention he relied on certain observations made by Patanjali Sastri, J. in A.K Gopalan’s case. The observations in question are found in paragraph 102 of the judgment. This is what the learned Judge stated therein:

“Read as a whole and viewed in its setting among the group of provisions (Arts. 19-22) relating to “Right to freedom”, Art. 19 seems to my mind to presuppose that the citizen to whom the possession of these fundamental rights is secured retains the substratum of personal freedom on which alone the enjoyment of these rights necessarily rest……… But where, as a penalty for committing a crime or otherwise the citizen is lawfully deprived of his freedom, there could no longer be any question of his exercising or enforcing the rights referred to in cl. (1). Deprivation of personal liberty in such a situation is not, in my opinion, within the purview of Art. 19 at all but is dealt with by the succeeding Arts. 20 and 21. In other words, Art. 19 guarantees to the citizens the enjoyment of certain civil liberties while they are free, while Arts. 20-22 secure to all persons—citizens and non-citizens—certain constitutional guarantees in regard to punishment and prevention of crime. Different criteria are provided by which to measure legislative judgments in the two fields and a construction which would bring within Art. 19 imprisonment in punishment of a crime committed or in prevention of a crime threatened would, as it seems to me, make a reductio ad absurdum of that provision.”

We fail to see how these observations lend any assistance to the contention that the “personal liberty” guaranteed under Article 21 is a guarantee against total deprivation of that freedom. Quite naturally, Mr. Keshava Iyengar very strongly relied on the decision of the Madras High Court in V.C Row’s Case in resisting the present applications. Therein the petitioner did not appear to have relied on Article 21 of the Constitution. Their Lordships did not consider the question whether right to travel abroad is a fundamental right guaranteed by Article 21. Further, that decision proceeded on the erroneous assumption that no passport is required for citizen of this Country to enter this Country. We are of the opinion that the decision in question does not lay down the law correctly.

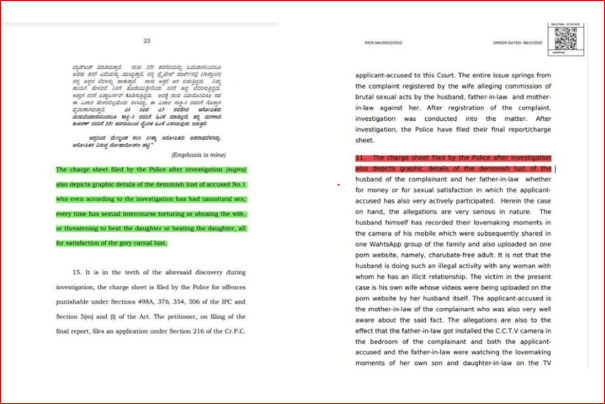

For the reasons mentioned above, we are of the opinion:— (i) the petitioners have a fundamental right under Article 21 to go abroad; (ii) they also have a fundamental right to come back to this Country; (iii) their right to go abroad is placed in jeopardy by the Government issuing instructions to the travel agents and carriers not to take on board passengers leaving India without valid passports; and (iv) either by convention or law most, if not all, countries do not permit a foreigner to enter them unless he possesses a valid passport issued by his country.

Article 21 is a mandate to the Government. It requires the Government not to deprive any person of his life or personal liberty, except in accordance with the procedure established by law. Admittedly, there is no law prescribing the procedure in the matter of granting passports. There is also no law prohibiting travel abroad. The “personal liberty” guaranteed by Article 21 can only be deprived in accordance with the procedure established by law. It cannot be deprived by any executive action taken by the Government.

For the reasons mentioned above, we are of the opinion that the Government by refusing to issue the passports asked for by the petitioners have deprived the petitioners their “personal liberty”, and thereby they have infringed Article 21 of the Constitution.

There appears to be basis for the complaint of the petitioners that by refusing to issue the passports asked for, the respondents have contravened Article 14 of the Constitution. It was complained on their behalf that the Government had exercised its power to issue passports in an arbitrary manner and that very arbitrariness creates inequality before law. But that allegation was denied on behalf of the respondents. As mentioned earlier, there is no law regulating the issue of passports. It does not appear that there is even an executive order regulating the same. A mere statement by a Minister to the Government cannot be considered as an order issued by the Government. There is no order issued in the name of the President nor one signed by any of the Secretaries to the Government. Therefore, the plea that the Government has made a reasonable classification does not arise for consideration. That apart, even the classification said to have been made cannot be considered as a reasonable classification taking into consideration the object intended to be achieved by the Government. In the counter-affidavit filed on behalf of the Government, it is stated:— “there has been recently a growing tendency among Indian Doctors to go abroad for purposes of employment or higher studies. In view of the acute shortage of trained medical personnel in India, our country can ill afford to spare the services of these doctors.” From the above statement, it appears that the Government is desirous of retaining the services of trained medical personnel in this country. If that be so, we fail to see any relevency in Government allowing Doctors who are in the employment of the Government or semi-Government to go abroad for higher studies on their undertaking to return, and serve their employers for a minimum period of three years. Bearing in mind the object the Government has in view, we fail to see what difference there could be between those Doctors who are in the employment of the Government or semi-Government Institution and others. The differentiation made between the two classes of Doctors mentioned above, appears to be arbitrary taking into consideration the subject intended to be achieved. As held by the Supreme Court of America in Marie Elizabeth Beg v. Frances Perrins refusal to issue a passport on irrelevant grounds amounts to a hostile discrimination. As observed by the Supreme Court in Bidi Supply Go. v. Union of India it is now well established that while Article 14 forbids class legislation, it does not forbid reasonable classification for the purposes of legislation; in order, however, to pass the test of permissible classification two conditions must be fulfilled, namely, (1) that the classification must be founded on an intelligible differentia which distinguishes persons or things that are grouped together from others left out of the group and (2) that differentia must have a rational relation to the object sought to be achieved by the statute in question. In other words, what is necessary is that there must be a nexus between the basis of classification and the object of classification.

The above Rule applies not only to classifications made under any statutory provision but also those made under executive orders. On this question again we are in respectful agreement with the decision of the Bombay High Court in Choithram’s Case.

In these petitions, it was stated that whereas the Government had refused to issue passports to the petitioners, at the same time, it had issued passports to (1) Dr. T. Nagakumar Shetty; (2) Dr. (Miss) Geetha Sreenivasachar and (3) Dr. (Miss) Rajalaxmi who were similarly situated as the petitioners.

In the reply affidavit filed by S.S Sadashiva Rao (petitioner in W.P No. 532/65) it was stated that in addition to the persons mentioned in the main affidavit, one Dr. A. Narayana Reddy, who passed his M.B.B.S, Degree examination in January 1963, had been given a passport to go abroad during the pendency of these petitions. As regards the case of Dr. A. Narayana Reddy, the respondents had no occasion to have their say, as that instance was mentioned in the reply affidavit. Hence we have not taken that instance into consideration.

Now coining to the other persons, this is what is stated in the counter-affidavit:

“The 3rd respondent granted passports to Dr. T. Nagakumar Shetty on 23-10-1964 to undergo training in Evangelical Dreaconese Hospital Detroit, U.S.A, on 23-10-1964, to Dr (Miss) Githa Srinivasachar to undergo training in Evangelical Dreaconese Hospital, Detroit, U.S.A, on 17-11-64 to Dr. (Miss) Rajalaxmi to undergo training in the Mac Hoal Memorial Hospital Association, Illinois, U.S.A, on 20-11-1964. As the applications of the petitioners were received by the 3rd respondent after 25th November 1964, the third respondent had no authority to consider the case of the petitioners”.

It is stated in the counter-affidavit that by a letter dated 20th November 1964, all Regional Passport Officers were informed that they should not themselves grant passports to Doctors, but should refer all the cases to the Chief Passports Officers for being dealt with. The letter in question was received by the third respondent on the 25th November 1964 and it was therefore, that he stopped issuing passports from the date. There is no reason to refuse to accept the facts as stated in the respondents’ counter-affidavit. Hence, it cannot be said that the third respondent was guilty of any hostile discrimination against the petitioners, in refusing to grant the passports asked for by them. But, we have already come to the conclusion that the classification made is violative of Article 14 of the Constitution for the reasons mentioned.

The only question that remains to be examined is whether the petitioners are entitled to the Writ of Mandamus asked for. On their behalf, it was urged by Mr. Ethirajulu Naidu and Mr. Shetty that by refusing to grant the passports asked for, the respondents have contravened both Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution; a duty is imposed on them by the Constitution to so formulate their policy as to not to infringe the guarantee of equality before law and further the Government is required to protect the ‘liberties’ guaranteed by Article 21 of the Constitution; they having failed to fulfil their duty, the petitioners have a right to ask this Court to issue a Writ of Mandamus to the respondents requiring them to comply with the requirements of the Constitution. On the other hand, it was urged on behalf of the respondents that the petitioners have no legal right to get passports and no duty is cast on the Government to issue possports to them and therefore a Writ of Mandamus cannot be issued.

For the reasons already mentioned, we are of the opinion that a duty is cast on the Government to protect the “personal liberties” guaranteed by Article 21. Similarly a duty is cast on the Government to treat all persons similarly situated, equally. If the Government fails to discharge those duties, it is for this Court to compel the Government to obey the mandate of the Constitution.

In Dr. Rai Shivendra Bahadur v. Governing Body of the Nalanda College the Supreme Court held that in order that mandamus may issue to compel any person or authority to do something, it must be shown that person or authority has a legal duty to do that thing and the petitioners have a legal right to enforce the performance of their duties. For the reasons already mentioned we think that the facts of these cases fall within that Rule.

Dealing with the judicial control through Mandamus, this is what A.T Narkase says in his “Judicial Control of Administrative Action in India” (at page 435):

“There is no doubt that judicial control through mandamus is the most difficult. This is because of the wide sweep of the remedy and partly from its very nature (being coercive). Unless the Courts are clear that there is an obligation imposed on the public authority for the doing or abstaining of the specific act a mandamus is not in order. If this principle is disregarded a discretion will be converted into an obligation by judicial legislation, to the great detriment of administrative efficiency and sometimes to the paralysis of governmental machinery. On the other hand if “clearly incumbent” duties are not discharged by public authorities for the benefit of the people and aggrieved individuals are disabled from getting justice because the courts interpret every duty as a power, bureaucratic tyranny will provail unchecked. Mandamus is the only efficient judicial weapon in this matter. Its role in the legal system is therefore delicate but extremely important. One of the obvious indicia of success or failure of judicial control of administrative action in a legal system of the Indian type is the working of mandamus. If it operates without producing administrative deadlocks on the one hand and official lethargy or tyranny on the other the function of court control is to that extent a success. When such a duty is found to be neglected or a power abused then mandamus has power, in the language of an English Judge “to amend all errors which lend to the oppression of the subject or other misgovernment” and is to be used when “the law has provided no specific remedy and good government require that there ought to be one”. Mandamus is “the supplementary means of substantial justice in every case where there is no other specific legal remedy for a legal right” and is intended ‘to apliate justice and to preserve a right.’”

In the cases before us, we are of the opinion that the Government has failed to discharge its “incumbent duties.”

For the reasons mentioned above, these petitions are allowed and in each of these petitions, a direction will be issued to the respondents to issue to the petitioner therein forthwith the passport asked for by him.

The petitioners are entitled to their costs in these petitions from the Respondents. Advocate’s fee Rs. 100.